Niku Games' Mala Sen on The Palace on the Hill, art and a hidden India

Studio co-founder Mala speaks to The Qun about subverting the form of farming games, making an indie game and more

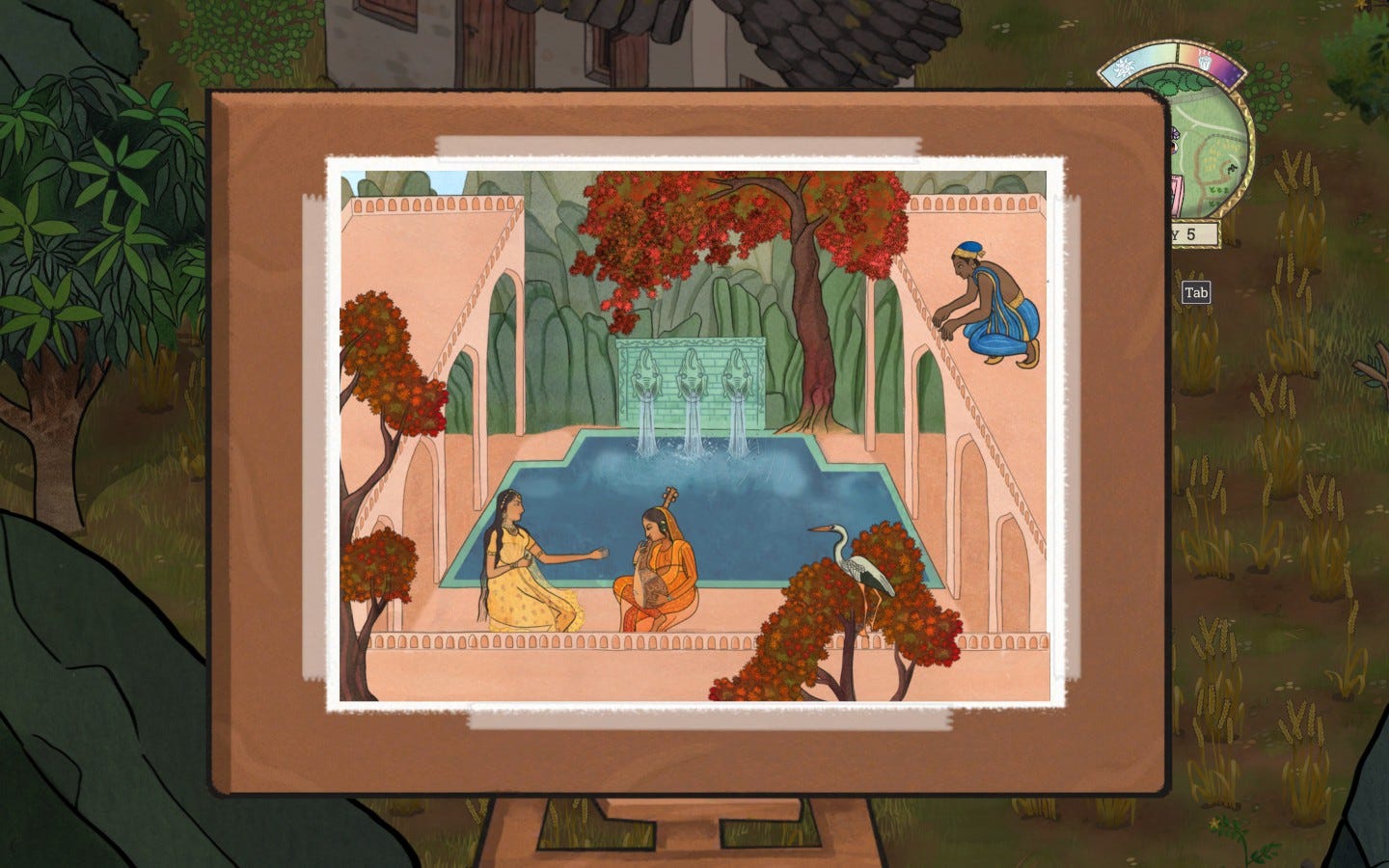

There’ve been games in the past that utilise the creation of artwork as a part of their bouquet of gameplay mechanics. Most recently, it’s Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora and its memory paintings that come to mind, but in that game it was used largely as… busywork between missions — for want of a better phrase. That said, I don’t recall having seen painting or drawing used as a central narrative tool in any of the videogames or visual novels I’ve ever played. And that is only one of the things that makes Niku Games’ The Palace on the Hill such a unique gem.

The game released on Steam on June 8, over a year after the playable demo (packaged as a prologue) went live on the same platform and on Google Play. Fun fact: The game was featured prominently in the recent Summer Game Fest’s Wholesome Direct 2024 and Women-Led Games showcases. I’ve been playing it for the past week, and I’ve a great deal of praise to lavish on it; but before we get to all that, what exactly is The Palace on the Hill? The trailer below’s a good place to start answering that question.

“I guess I would describe it as this experience of living in a village environment that is surrounded by all sorts of ruins and old palaces — and also go through the little narrative experiences of a kid while on his summer holidays,” says Mala Sen, art and visual design director of The Palace on the Hill and co-founder of Niku Games. “I mean, that’s not the elevator pitch,” she laughs, “But it was what I focused on while making the game. And on getting all the details that are close to me, a ’90s kid, right? And also, creating things that a person who also grew up in India at around the same time as me, can relate to.”

Inside the Palace

A cosy village sim with some authentic tasks to do across an almost-fully explorable village dotted with a host of interesting NPCs is an interesting premise in itself. But once the idea of of creating paintings as a key plot device and means of progressing the story is introduced, The Palace on the Hill takes on a life of its own. And quite unsurprisingly, the response thus far has been quite positive, particularly from those who aren’t regular gamers.

“A lot of people [we spoke to] who don’t regularly play games know of Candy Crush or PUBG,” Mala explains, “And their whole idea of what games are is very different, so they were quite happy and surprised to see a game that was all about art and narrative — and had nothing to do with winning or shooting anyone.” Noting that this is what most of the response thus far has been like, she adds, “People are of the view that this sort of game needs to exist.”

It’s not as though games about farming, running a restaurant or exploration don’t exist. However, all these aspects in a game that is set in a distinctly modern-day Indian setting is almost impossible to find. Throughout my time in protagonist Vir’s shoes, I found myself reminded of something Masala Games’ Shalin Shodhan said to me a couple of weeks ago. He described a common reaction among Indian streamers to his game Detective Dotson as ‘a summer vacation’, elaborating that it was “because they get a very warm, fuzzy and cosy feel from the game”. That’s precisely how I felt while playing through The Palace on the Hill — which is quite appropriate also because the game is set during Vir’s own summer vacation.

“It’s a different take on farming games, because it’s not about expansion and more expansion. Neither is it about someone who comes from the city to the village to build out a farm,” Mala continues, “This game is about a kid who is forced to do these jobs. He wants to go to the city, and wants to have a different kind of a life. It sort of turns the idea on its head of a farming game.” This thread of subverting tried-and-tested convention and form runs through various aspects of the game, whether that’s the approach to farming, the introduction of art as a key aspect or the take on city versus village debate (that has largely experienced a very one-sided portrayal in videogames).

A key reason for the warm reception received by The Palace on the Hill thus far, according to Mala, is its relatability. “People are happy to see a character, Vir, to whom they can sort of relate,” she says, “And also a setting to which they can relate.” Some of the things that instantly struck me about making things so much more relatable were the game’s groundedness, lack of pretension and authenticity. A case in point is how the hand pump — a water-lifting device of great importance in the game — works.

If you’ve ever used a hand pump before, you’ll know it needs to be primed before it releases any water. And the process for doing so entails pushing down on the hand lever, releasing it, pushing back down, releasing it again and so on, until the water level rises to the height of the discharge pipe and begins flowing out. It brought a smile to my face to see that the keyboard controls for doing so in-game were an accurate replication of the real world method: Push down button, release, push down again, release and so on.

“Anyone who’s actually used a hand pump will find it to be very realistic, “Mala concurs, “But earlier, when we’d pushed out the demo, we received a lot of feedback that people weren’t getting the hang of it.” Considering the vital role growing your own crops plays in The Palace on the Hill, an inability to procure water (and the absence of an alternate source of irrigation) would definitely be game-breaking. And so, a call was taken to allow players to hammer the button in order to fill up the meter and prime the pump. “We took the decision to allow players to do it the easier way, which is fine because we’ve had so many iterations with the hand pump,” she recalls.

The hand pump isn’t the only gameplay mechanic that has evolved over the time The Palace on the Hill has spent in development. “The attention to detail, the feel and the ambience of the game is something I’ve always wanted and stuck with, but the game mechanics have evolved as we got more of our friends to play the demo,” Mala points out.

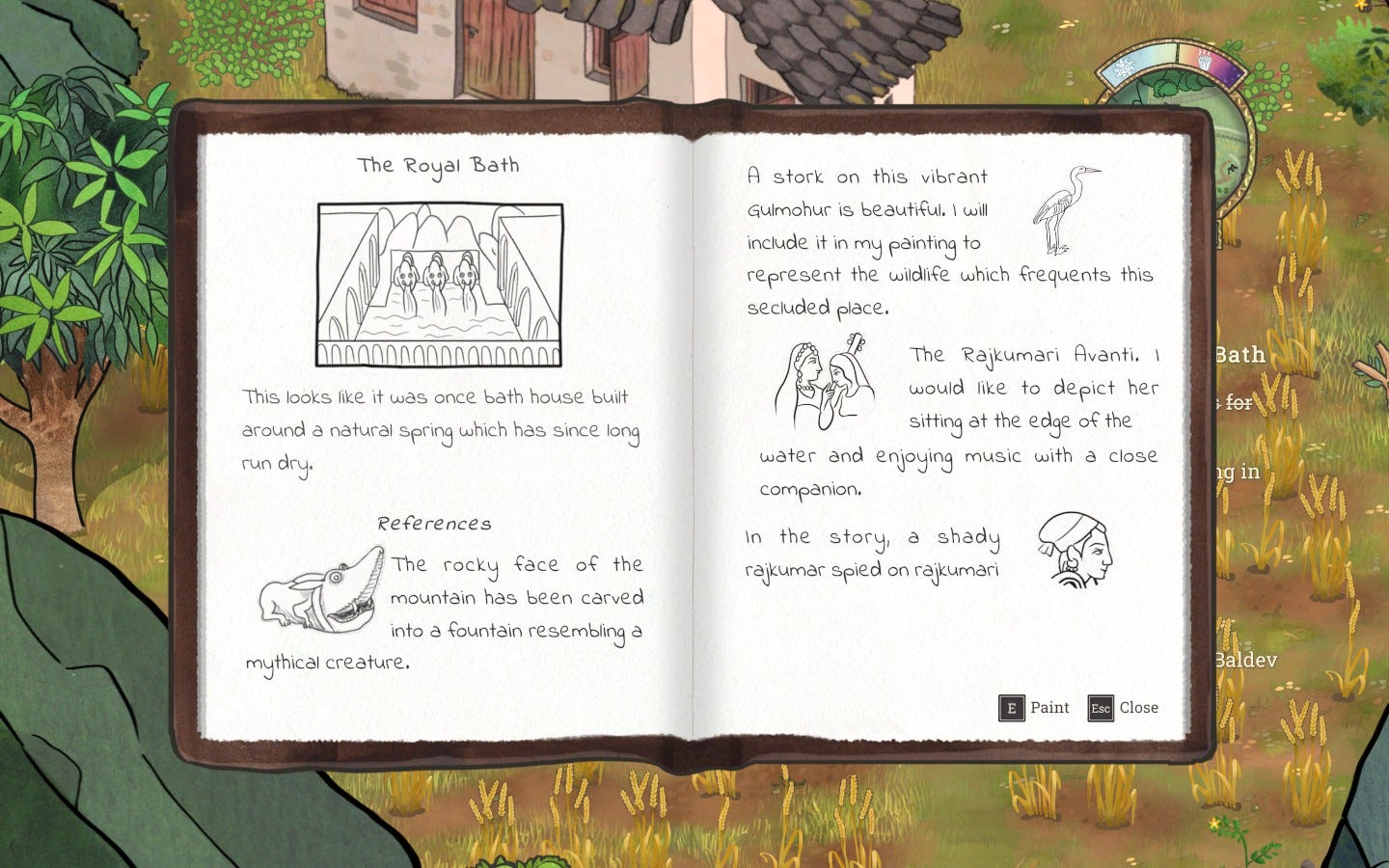

Such as? “There was this very interesting idea we had in the beginning,” she offers. The game’s X page, in case you’re curious, carries a post that elaborates on the original idea. “We had a very complicated art mechanic in the beginning which was all very dialogue-based. And the art would change based on the dialogue options and you had to try and figure out the best combination,” Mala continues, “But as we playtested it, we found that people weren’t really going through the dialogue and that they weren’t it that much.”

And so the decision was taken to leave out that mechanic and make it all about the story. “We decided to simplify it and make it a narrative within the narrative — like the story about this particular princess and how her story reflects on Vir’s own journey,” she explains, adding that the process of iterating various gameplay mechanics and simplifying them was a major part of the development process.

The journey

Niku Games comprises Mala and her partner Mridul Kashatria, who handles programming and game design. It was nearly a decade ago that the duo first crossed paths. “Before I got into game development, I was doing traditional art in the form of textile art, so these large-scale tapestries,” she recollects, “It was around that time that one of my friends introduced me to Indie Game: The Movie, which is when I realised there’s a lot of art in games.”

An interesting digression on the topic of Mala’s then-impending departure from textile art, The Palace on the Hill features a closed and (subsequently, I presume) derelict handloom factory. Was it, I venture, a visual metaphor for Mala’s altered career trajectory? “We had actually planned a character and quest based on the handloom, but ultimately we had to eliminate that,” she reveals, elaborating, “We liked the building and felt it told a story environmentally, which is why it’s still there. But I suppose it was planned because of my textile background.”

“I was kicking myself,” says Mala, “Why didn’t I see that there was so much art in games? This blew my mind and it got things churning — maybe there was something here that I could do. But I’m not a technical person and don’t know anything about programming, so I abandoned that thought.” This would be temporary, because in 2015 (a whole five years before the concept of the game was finalised), the Niku Games co-founder would find herself at a pen-and-paper Game Jam organised by a friend of hers in Bengaluru.

“That was where I met Mridul and we hit it off,” she says, “At that time, he was also looking to get into game development. Prior to this, he had co-founded a company where they digitised newspapers. It was a successful company with around 2,000 news publications put online in a digital form, but he wanted to try something new.”

“Next, we thought, ‘Okay, programmer and artist, what more do we need?’. Soon, we learned the hard way that there was so much more to it,” continues Mala, “But that’s when we started, and I decided to leave the art world behind. The career shift was one that really appealed to me also because the art world is a lot about owning pieces of art. Games are interactive and anyone can enjoy them — I liked the idea of people interacting with my art and getting lost in it.”

The realisation that developing games would need a bit more than just a programmer and artist led to the Niku Games duo relying on collaborators. “Other than the two of us, we have Srikant Krishna who does our music. We’ve also had a very good friend of mine Mithun Balraj help out on narrative, character building, QA and things like that,” she lists, “Plus, we’ve had people help us a bit of additional art and with playtesting.”

Just a few minutes into the game, all of these pieces — the programming, the music, the characters and of course the art — begin to come together beautifully and transport you to a corner of India you’ve perhaps visited in this life or another. “The Palace on the Hill was based on the idea of a village surrounded by ruins that nobody knows about,” Mala says, “There’s no official story, but if you ask the locals — like in so many villages you’ll encounter when you travel across the country, they’ll tell you a scandalous story.”

Tales of kings and queens, mysterious disappearances overnight, new monarchs being crowned by morning, a kingdom in disbelief, an heir in strife and conflict all around — these are par for the course. “Incorporating these gave a nice sense of adventure in a game that wasn’t fantasy, but one that was relatable, modern and based in an Indian setting,” she continues, “We didn’t want to make a larger-than-life mythological hero, just an everyday kid. And the idea really took seed when we were travelling in Rajasthan and saw this fort surrounded by ruins.”

As it turns out, the fort drew a large majority of the visitors, while no one was really visiting the ruins that looked like semi-completed buildings. “And these ruins were all located on rolling hills, so we went hiking to each of those,” Mala reminisces, “They were lonely, mysterious and beautiful all at once, and at the bottom of those hills, was a valley with a tiny village. And that was the inspiration for the setting.”

Having an inspiration and bringing it to life are two different things entirely, and in terms of the look of this world, it was Mala’s brushstrokes (physical and digital) that breathed life into it. “In the beginning, I thought of painting the game out on paper, but that made the whole process very rigid, as there was no space for editing and changing things up,” she says, adding, “But I still wanted that paper effect and storybook watercolour effect.”

And so, she painted large swatches of watercolour on paper in different colours. “So I have one big sheet each for reds, browns and greens, and I use them as textures for my drawings,” she says describing her process, “I draw digitally and use the colours as a background to ensure that watercolour effect. There is one part of the opening scene that was entirely painted on paper though and that is the distant palace in the background.”

Climbing up the hill and down the other side

Learning about how an indie game gets made is simultaneously fascinating and sobering considering the sacrifices that often have to be made in the quest to have your vision light up screens (of all shapes and sizes) worldwide. And funding is a major part of that . “This was our job, we weren’t doing anything else and were using our savings,” recalls Mala, “At the start, we were living in Bengaluru where we had to pay rent and the city’s high costs, while making different little prototypes and feeling our way through the whole game development thing.”

It was then decided that if the game was to be built sustainably, costs would have to be cut. “We then shifted to Coimbatore where my parents live, and stayed with them for a while, which really lowered our costs,” she says, “That way we were able to work on the game full-time. And last year, we got some grants including ID@Xbox, and we were part of the Wings Elevate programme — all of which brought in some money to help with the last bit of development.”

As far as post-launch plans go, Mala discloses that Niku Games is looking at porting the game to Xbox and providing the option to play the game in a number of Indian languages (currently, you can do so in Hindi and Bengali). Before we call it a day, I’m curious to know the one key thing she’d like players to take away from their experience in The Palace on the Hill.

“That’s a tough question,” she says, “I would want them to feel like they’ve experienced a little slice of this very Indian-flavoured experience. I would like them to enjoy the ambience and take it away with them like, ‘Yeah, I had a nice time living in this little world for a while’.”

The Palace on the Hill is currently available for PC and Mac (Steam)